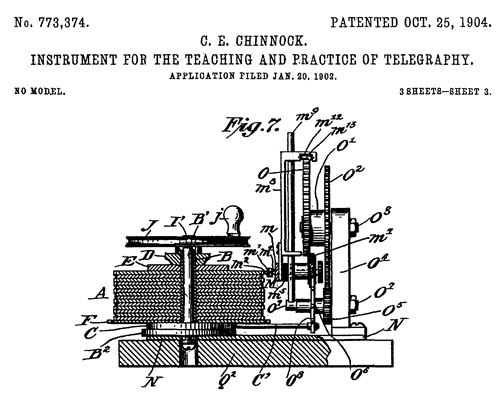

Students learning Morse code have

had a variety of commercially made practice instruments

available to them over the years to assist in their studies.

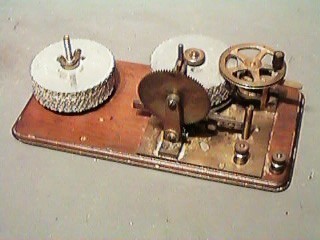

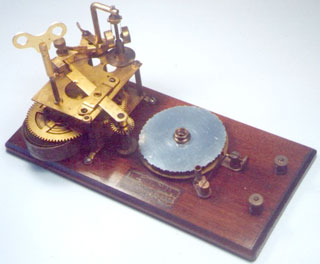

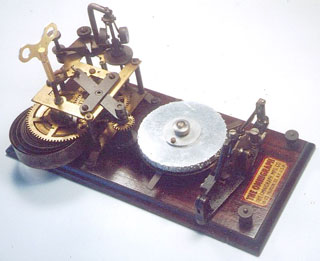

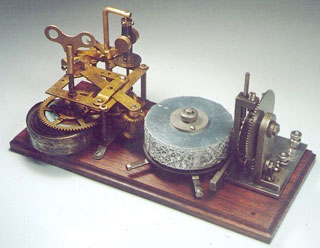

Such devices included purely mechanical sounders that simulated

the audio of a working sounder (fig. 1), inexpensively made

sounder/key combination sets identical in function to the more

robust instruments for commercial use, a variety of perforated

tape devices such as the Instructograph, Teleplex, AA

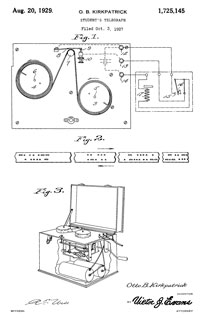

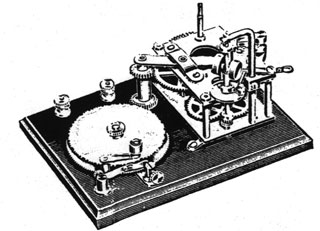

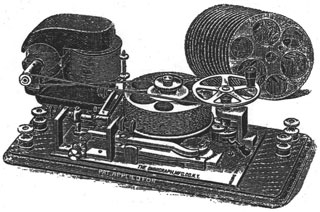

Transmitter, and others, a rotating painted cylinder device

called the ‘Natrometer’ (

fig. 2), as well as

a variety of 78 RPM and later 33 RPM records and tapes.

Fig. 1: “No. 1 Mechanical Telegraph

Instrument” is the name for this device in the 1912 J.H. Bunnell

catalogue. Bunnell made another variety of mechanical sounder,

and a number of other manufacturers also made such purely

mechanical instruments including Manhattan Electrical Supply

Company, and British companies.

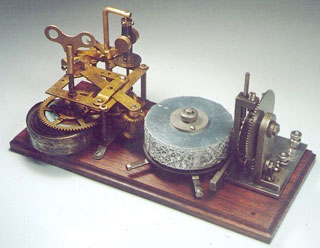

Fig. 2: Natrometer. A clock motor drives a

rotating aluminum drum painted in dielectric (insulating) paint.

The unpainted surface is in the shape of continental code

characters. A stylus in contact with the surface of the

drum automatically travels from one line of Morse code to the

next higher line and then back down the lines of code.

Current generation Morse code practice instruments employ

microprocessorcontrolled random character generators capable of

almost any sending speed. PC based software programs for

learning Morse code are also widely available. Among the

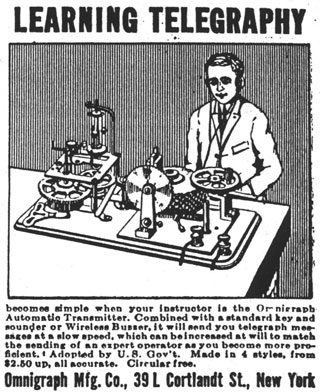

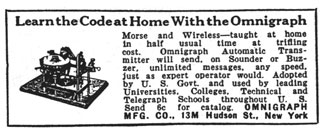

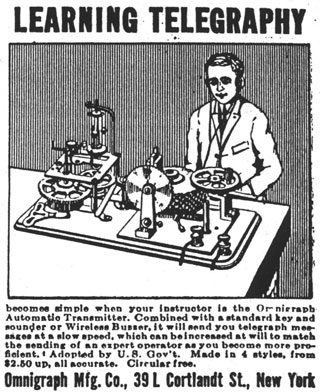

most unusual Morse code practice devices were those manufactured

by The Omnigraph Manufacturing Company in New York City between

1900 (

1) and 1931 (

2). As

best as can be determined, the Omnigraph company never produced

anything other than Morse code practice devices, and did not

produce commercial devices such as telegraph keys or sounders of

any sort. Omnigraph advertisements were featured in numerous

telegraph, radio and electrical publications of the day

including QST, The Wireless Age, Modern Electrics, The

Electrical Experimenter, Journal of the Telegraph, Radio,

Electrician and Mechanic and probably others (

3).

Omnigraphs were also marketed by major retailers of the day

including Sears and Roebuck, J. H. Bunnell, Manhattan Electric

Supply Company (‘MESCO’), and Wholesale Radio Service Company

(New York City). The factory occupied several different New York

City addresses over the 30+ year span of the company existence,

judging from the addresses listed in the numerous advertisements

during this time period. The 1914 and 1919 U.S. Department

of Commerce rulebooks stated that commercial and amateur radio

license examinees undergo a code test that: “shall consist of

messages with call letters and regular preambles, conventional

signals and abbreviations, and shall in no case consist of

simple, connected reading matter. The test will be conducted by

means of the Omnigraph or other automatic instrument wherever

possible (

4)”. The demise of the company

and its unique instruments was undoubtedly related in part to

the superior capabilities, versatility, and reliability of

perforated tape devices such as the Instructograph. As dazzling

as Omnigraphs were to watch in use, they were finicky and

temperamental instruments to use. The multi-disc Omnigraph

devices (see below) although ingenius in design, allowed for, at

best, pseudo-random code generation, limiting overall utility.

Although company advertisements boasted a 45 minute running time

on a single winding, a properly functioning and adjusted

instrument would begin to slow noticeably after about 20 minutes

running time (

5).

The Instruments

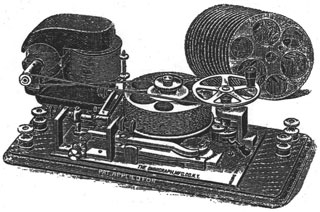

The company manufactured a number of instruments of varying

complexity, all of which had rotating aluminum discs with Morse

code characters incised into the edges of the discs as raised

teeth. As the disc rotated, a tracking stylus in contact with

the teeth was displaced by the raised teeth, and allowed an

electrical contact to make and break a circuit, producing the

Morse code characters. The instruments varied only in whether

the discs turned by use of a hand crank or were motor-driven,

and in the numbers of discs that could be stacked, necessitating

a cam mechanism which raised and lowered the tracking stylus in

the multi-disc models. Some instruments included keys, sounders,

or buzzers integral to the devices, although the company also

sold ‘stand-alone’ sounders, buzzers, batteries, and hookup wire

produced by other manufacturers as accompaniments to their

instruments. A student could purchase the Omnigraph instrument

alone, however for a few dollars more, the student could obtain

a package that

included a learner’s manual, a battery, a sounder or buzzer,

some wire, and a straight key. Although the company

advertisements described 5 models of Omnigraphs, (

Table 1), in reality, at least 15 distinct

instruments were advertised or produced over the years.

TABLE 1: Omnigraph Company Instrument

designations

| COMPANY DESIGNATION |

DESCRIPTION |

VARIATIONS |

| No. 1 Omnigraph |

Transmitter only or

transmitter/KOB combination

|

Two versions (figs. 7,9)

|

No. 2.Omnigraph

|

5 and 15 disc versions

|

5 disc model-four types

(figs. 12-15).

15 disc model-six types (figs. 19-24.)

|

No. 3 Omnigraph

|

Single disc transmitter

model with hand crank.

|

One version (fig. 8). Similar to Omnigraph

No. 1 (fig. 7)

but larger size wooden base.

|

No. 4 Omnigraph

|

5 disc model with key,

buzzer, and provision for headphones |

Two versions, (included

in No. 2 variations, above). (figs. 13,15)

|

No. 5 Omnigraph

|

Single disc model with

hand crank and clock motor

|

Two versions (figs. 10,11)

|

The instruments were mounted on wooden bases, which on most

models measured 5” X 10-1/2”. Many but not all instruments bore

a company identification label. Some were decals applied to the

wooden bases while others were metal tags attached by small pins

hammered into the wooden bases.

The company supplied Omnigraphs to others who affixed their

names to the instruments including the National Wireless

Institute (a study-at-home correspondence school) in New York

City, and A. W. Gamage, Ltd., London. Most Omnigraphs have

the notation ‘Patented’ or ‘Pat.’ embossed into the wooden

bases. A c. 1910 Omnigraph catalogue has a diagram of a No. 5

instrument bearing the patent date Oct. 25, 1903. The only

instrument with a patent date encountered by the author was a

5-disc instrument bearing the patent date of Oct. 23, 1904. To

the best of the author’s knowledge, there has been no research

on the patents held by the company nor on the individuals who

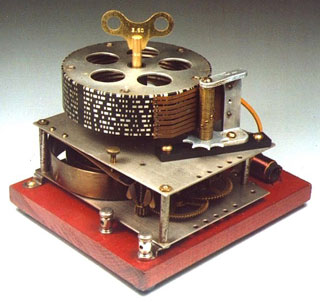

designed instruments. Discs The unique feature of the Omnigraph

instruments is the use of rotating aluminum discs with raised

teeth on the edge in the shape of the actual Morse code

characters. Discs were of at least 3 different types (figs.

3-

5) and a fourth type

that appeared in an advertisement (

fig. 21)

but which has never been seen by the author.

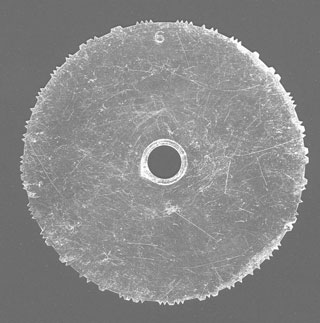

Fig. 3: A typical disc from a multidisc

instrument. Notice the 5 concentric holes in addition to the

central spindle hole. In use, besides the central spindle post,

a second post must be fitted into one of the 5 holes to align

all the discs in the stack in a uniform manner to allow for

coherent messages that were spread over more than a single

disc. This disc is marked 9-O, representing the 15th disc

of the 9-series of discs. (The letter ‘O’ is the 15th letter of

the alphabet). Transcription of the Continental code reads: “SEE

SILAS FLA HEY ABOUT 5 AND 35 SIG W LEE”

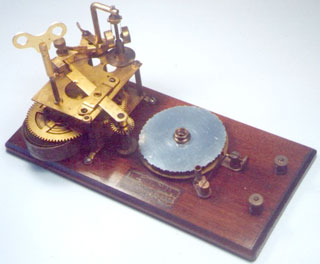

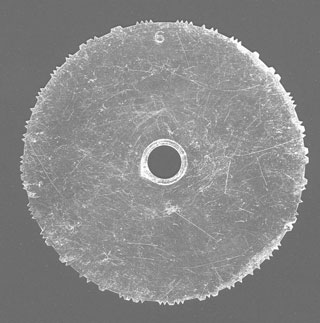

Fig. 4: A typical disc used on a single disc

Omnigraph instrument. A single central spindle hole holds the

disc onto the rotating platter. This particular disc is marked

“6”. Transcription of the American Morse reads: “HR STMH

FM NEW YORK 21 TO ADH. YES SIG LH”

Fig. 5: An unusual disc, with a central

spindle hole and two alignment holes. This disc is one of a

complete set of 15 found on the instrument shown in

fig. 23. This disc is the last disc (‘O’)

from the series, and bore no numerical designation. The

character consisting of 4 short dashes at approximately the 2:00

position on the disc is the Morse character denoting a new

paragraph (6). Translation of the Morse message reads:

“ON SALE CAN YOU SEE? ANSWER SIG L RICHARDS”

The discs were all 3-1/8” in diameter and were either thin

(1/32”) or thick (1/16”). Thin discs were used on the single

disc instruments, and had a single central hole for the spindle,

whereas thicker discs were used on the multidisc instruments,

and had alignment holes in addition to the central spindle hole.

Close inspection of the discs indicates that production involved

cutting the discs, analogous to a locksmith duplicating a key.

Such an arrangement would produce a disc with closer dimensional

tolerances than stamping discs from a die.

Discs were available for both American Morse and Continental

code. The number of characters on any individual disc varied

from 12 to 36 (

4) with the lower number of

characters allowing for slower code speed in the beginning

lessons and the closer spaced characters for more advanced

lessons. The speed of rotation of the discs, of course was user

modifiable, allowing further control of sending speed. Code was

sent using the ‘Farnsworth Method’ indicating that the

individual Morse code characters were uniform in dot and dash

length and spacing with slower code speeds achieved simply

allowing more time between individual characters. The thicker

discs could be used on the single disc instruments but the

thinner discs were physically incompatible with the multi-disc

mechanism, which required a second alignment hole. Practice

sessions included code groups, random characters, numbers,

punctuation, and short messages (

fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Transcription of the full disc series

of Continental code for the 7-series of discs.

(Transcription courtesy of Mr. Lynn Burlingame N7CFO).

7-A

|

III

SS AS HOOKER OFF LB NJ SEPT 15 TOT

|

7-B

|

BROWNS

OPR

STR BRITTON VIOLENT RAIN AND

|

7-C

|

WIND

STM RAGED AT ASBURY SE OF US THIS MNG

|

7-D

|

DAMAGED

THE

TOWN AVON. 2 LIVES IN PERIL

|

7-E

|

BY

FIRE ON SHIP KENNEDY BEACHED HERE. B

|

7-F

|

GEO

DENTY

KEY ESCEBETTS FRANK R. MILLERS

|

7-G

|

JOE

TEER JOHN Z. WORTON SAMUEL T. CORBIN

|

7-H

|

NAMES

FM POCKET OF ROB BENTLY SAVED,

|

7-I

|

TURKISH

HUSSARS

ARRESTED WHILE AT SCUTARI

|

7-J

|

MAN.

Q HIGGINS ON STEAMSHIP XE MEYER.

|

7-K

|

RECD

FM HATTARAS WED. 5 AM SEVENTEEN HUNDRED

|

7-L

|

WT

IS ZN HOPING FOR ? S FORD IS A VYGD

|

7M

|

.

IT WAS STATED IN ADVICE S. MURAD WAS PUT

|

7-N

|

TO

DEATH D’S NO IS 496 ADSMEAT 370N

|

7-O

|

SEA-AIR AVE 7 AM (SIG C HAROLD EBLIN.

|

Discs that were used on multidisc instruments (5 or 15 disc

models) were designated with an alphanumeric numbering system

consisting of a number followed by a letter between A and O

accounting for the 15 discs in the series. Other discs (

fig. 4) were designated simply by a number. A

set of 15 discs exists that is labeled A through O with no

number designation (

fig. 23).

It is not known with certainty but it is suspected that the

discs for single-disc instruments were numbered whereas the

discs for instruments employing multiple stacked discs bore the

alphanumeric designations. Alphanumeric discs are known up the

‘9’ series however it is unknown if more than 9 sets of discs

exist. The lowest numbered series of discs (series 1 and 2 for

example) had simple code groups whereas the highest numbered

series (

8 and

9) had more

complex messages including numbers and punctuation characters.

Nine sets of 15 discs may exist for both Morse and continental

code for a total of 135 discs for each code. The highest

numbered disc encountered by the author is ‘19’, suggesting that

at least 19 numbered discs exist.

Discs from the “2” series exist for both Morse and Continental

code, and transcription indicates that the messages were

completely different indicating that the Morse and Continental

code discs were not simply the same messages in Morse and

Continental code.

Morse discs were identical in appearance to Continental code

discs and the company made no attempt to differentiate one from

the other based on appearance. The only way to tell Morse from

Continental discs is to visually inspect the discs, looking for

the characteristic Morse characters that were distinct form the

continental code characters.

In addition to the discs that were included with the initial

purchase of the instrument, additional discs could be obtained

at modest cost. The company also permitted students to exchange

their discs for different ones for a 2 cent per disc postage and

handling fee. If one ordered 5 extra discs for a 5 disc

instrument, it is suspected that the student would receive the

first, second, or third set of 5 discs of a 15 disc sequence.

Transcription of the discs has demonstrated that sometimes the

company mislabeled the discs. A 7-L disc owned by a collector is

the same as a 7-I disc in the author’s collection. Other

collectors have other discs with the same messages on discs with

different alphanumeric designations suggesting incorrect

labeling. The author has several alphanumeric discs with the

letter crossed out and another letter stamped next to it as a

correction. Another disc has the letter designation on the disc

upside down. The finding of inconsistent and erroneous labeling

of discs suggests that disc labeling was not automated, and that

human errors were not rare in labeling discs.

The author’s experience and the anecdotal experience of other

collectors is that most discs encountered are the thicker discs

used in the multidisc instruments. The 6 thin discs in the

author’s possession are all American Morse.

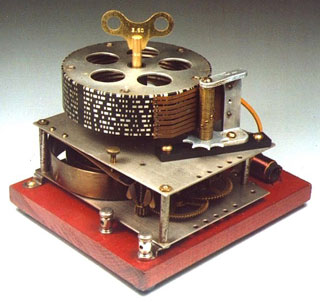

The Clock Motors

Another feature of some of the Omnigraphs is their use of a

spring-driven windup clock motor. An interesting adaptation is

the use of a flying-ball governor mechanism to maintain constant

speed in the face of a marked increase in the instantaneous

loading, as when the stylus tracking mechanism moved from one

disc to a higher disc in a stack. In reality, the sending speed

slowed as the tracking stylus moved to a higher disc, and

frequently would flub the first character on the higher disc. As

the stylus descended the stack of discs, frequently it would

skip the adjacent disc and track to a lower disc, although this

may have been secondary to wear on the cam mechanism. The clock

motors on different instruments varied slightly in design over

the years but all had the flying ball governor, and a friction

speed control mechanism. An experienced clock repairman

indicated to the author that the clock motor resembles a Seth

Thomas clock mechanism of the era with the addition of the

governor, and that most likely Seth Thomas provided the clock

drives to the Omnigraph company. The motor mainspring is

presently an off-the-shelf item from clock repair parts sources

and can easily be obtained and replaced on existing instruments

if needed.

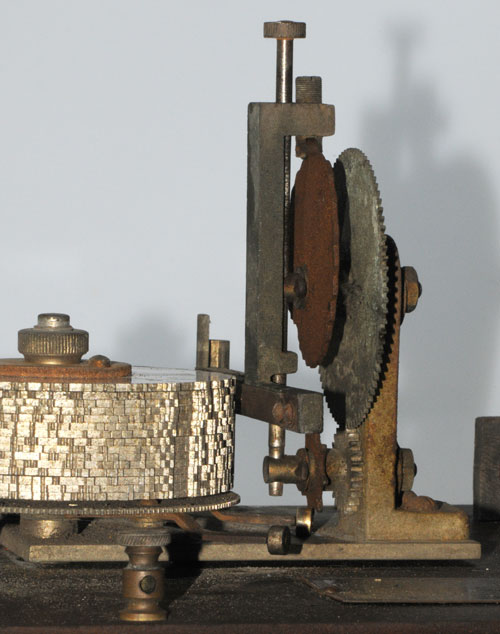

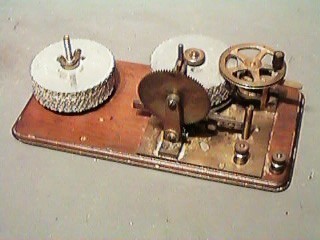

The Simplest Omnigraph

The simplest Omnigraph device consisted of a single disc mounted

on a platter which was rotated by use of a hand crank (

fig. 7).

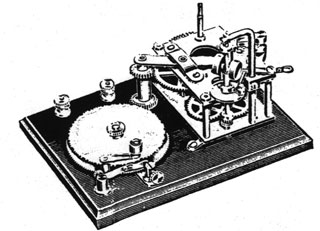

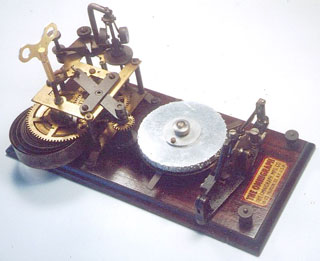

Fig. 7: “Omnigraph Transmitter No. 1”, the

simplest device the company produced. The user had to supply his

own battery, buzzer or sounder, wire, and key.

Advertisements in 1909 listed this model as “The Omnigraph

Transmitter No. 1”. The single disc supplied with the instrument

had American Morse characters which sent the nonsense statement:

JOHN QUICKLY EXTEMPORIZED FIVE TOW BAGS, which incorporates all

26 letters of the alphabet into one sentence. No numerals or

punctuation were included. An instruction booklet “How To

Become An Excellent Operator” was included with purchase of the

device. Additional discs could be purchased for 5 cents each.

The same device on a larger base was known as “The Omnigraph #3”

in a c. 1910 catalog (

fig. 8).

Fig. 8: “Omingraph Transmitter No. 3” is the

same instrument on a larger wooden base. From a c.1910

Omnigraph Company catalogue.

Omnigraph KOB

A device similar to the simplest Omnigraph (above) incorporated

an inexpensive sounder and key identical to the J.H. Bunnell

“Morse Learners’ Outfit” advertised in the 1900 Bunnell

Catalogue, and were undoubtedly supplied to Omnigraph by

Bunnell. (

fig. 9).

Fig. 9: Omnigraph transmitter with integral

key and sounder. This instrument is missing the hand crank used

to turn the platter containing the disc.

There was no separate model number for this device, and it was

regarded as a version of “The Omnigraph Transmitter No. 1.” The

1903 MESCO catalogue listed this device as “Omnigraph Learner’s

Set”. A ‘press release’ in the April 16, 1901 issue of The

Telegraph Age described this device suggesting that it may be

the first instrument produced by the company.

Single Disc Omnigraph with hand crank and motor

Due to the inconvenience of having one individual hand crank an

instrument while another listens to the code, (or even worse,

trying to crank it yourself

while attempting to copy Morse code), the company supplied a

device that allowed both for hand cranking and motorized disc

rotation (

fig. 10).

Fig. 10: “Omnigraph No. 5” is the company

designation for this model. At $7 around 1915, it came with a

total of 3 discs and a learner’s manual. This instrument is also

missing the hand crank as is

fig. 9.

The logic behind supplying such an instrument is unclear,

inasmuch as the hand-cranked mechanism would seem completely

superfluous in the face of the convenience of motorized use.

Despite the ease of having automated disc turning, the user was

still limited to a single disc at a time, and by having to

change the disc after every use. It must have been very tedious

for the student to listen to the same disc over and over, and to

have to change every disc by hand. It is speculative, but

undoubtedly at least some students thought to turn the disc

over, thus playing the disc backwards, generating new

characters. The letter A (.-) for example would then become N

(-.). A c. 1930 company catalogue illustrated a slightly

different version of this instrument on a smaller base and with

a more compact design (

fig. 11).

Fig 11: “Omnigraph No. 5” on a smaller base

with more compact design than

fig. 10.

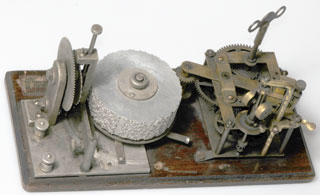

Five Disc Model

The 5 disc model was designated “Omnigraph No. 2 Junior” in the

1924 J.H. Bunnell catalogue. The five disc model (fig. 12) was

probably the most popular model (4), and incorporated the clock

motor, a stack of 5 discs, and a cam mechanism to move the

stylus from one disc to the next higher disc.

Fig. 12: “Omnigraph No. 2 Junior” is the

company designation for this model, and is reported to be the

most popular model sold (

4). A buzzer was

included in the purchase price of $12.50, or for $14 the device

came with a key and sounder, battery, wire, and a learner’s

manual.

When the stylus arrived at the highest disc, it would travel

down the stack again from the highest disc to the lowest disc

and then ascend again. An adjustable mechanism allowed the user

to decide whether to play the entire disc before moving to the

next disc in the stack, or to play a segment of the disc before

moving to the adjacent disc. 1/5, 2/5, 3/5,4/5 or the entire

disc could be played before moving on to the next disc. By

allowing less than a full disc to play before moving to the next

disc, the user could create nonrepeating messages much longer

than the sum of all of the characters on the 5 discs. For

example, if the user wished to play only 2/5 of the disc before

moving on to the adjacent disc, then when the disc reached the

highest level, it would begin to descend down the stack of discs

again, and would play a different 2/5 segment of each disc on

the way down. At the lowest disc, the stylus would begin to

ascend the stack of discs again, this time playing a 1/5 segment

of the disc that had already been played with the last 1/5

segment of the disc that not been played. This ingenius

pseudo-random character generator design would allow continued

playing of different 2/5 disc segments for many, many hundreds

of characters before repeating the message. By adjusting the

device to change discs after 1/5 of a disc, then 2/5, 3/5, 4/5

or a complete disc, students could produce a nearly infinite

number of non-repeating characters before repeating. Of course

shuffling the disc order, flipping the discs over, or rotating

one or more of the discs ‘out of phase’ with each other would

allow even more variety. Nevertheless, students may have

relatively quickly memorized segments of discs, diminishing the

utility of the device as a learning tool. The company also

manufactured a 5-disc device with a key and buzzer (

fig. 13).

Fig. 13: Omnigraph No. 2 Junior with

integral buzzer, key, and provision for use with earphones.

|

The governor is missing from the spring motor as is the

cover for the buzzer.

|

Advertisements for the 15 disc version of this device show

earphones being used. The small cylindrical object next to the

buzzer is a primitive coupling transformer for use with the

earphones described in a c.1930 company catalogue as “induction

coil #21”. The primary winding is in series with the buzzer, and

the secondary is connected to the earphone terminals. The audio

heard in the earphones would be the same frequency as the buzzer

and would be expected to mimic the raspy audio quality of spark

transmitter signals of the era. A similar coupling device is

present on the Natrometer (

fig. 2), and is

also present on a similar device advertised in a c.1919 Gamage

catalogue. The buzzers included on the Omnigraph devices so

equipped were almost certainly manufactured by Signal Electric

Company of Menominee, Michigan. Another version of the 5

disc model had the discs stacked on top of the motor (

fig. 14) in a compact arrangement.

Fig. 14: Compact 5-disc device.

Advertisement from an issue of QST c.1920’s

As best as can be determined, there was no separate model

designation for this device. A version of this model included a

buzzer and key (

fig. 15) similar to

fig. 13, and was manufactured for use by the

New York Wireless Institute, and which bore their name (

fig. 16).

Fig. 15: Compact 5-disc Omnigraph with

integral key and buzzer made for the New York Wireless

Institute. (Photo courtesy of Mr. Lynn Burlingame N7CFO).

Fig. 16: Label on device shown in

fig. 13.

Although the New York Wireless Institute was a study-at-home

correspondence school, advertisements mention an on-site ‘post

graduate’ course. It is unknown how many students actually

studied at the ‘campus’. Of note, the address of the New

York Wireless Institute was 258 Broadway.

Between about 1910-20 the Vibroplex Corp. factory was located

directly across the street at 253 Broadway. Students enrolled in

the Wireless Institute ‘post graduate’ course of study wishing

to purchase bugs could conveniently do so at the Vibroplex

factory. Of interest, a c.1930 Omnigraph catalogue listed

Vibroplex bugs for sale including the #4 model (“Blue Racer”)

for wire work and the #6 model (“Lightning Bug”) for wireless

work.

A typical 5-disc model Omnigraph was listed in a c. 1919 A. W.

Gamages (London) catalogue (

fig. 17) under

the name “The Dictamorse No. 1” and bore a Gamages label (

fig. 18).

Fig. 17: Typical No. 2 Omnigraph listed in a

c.1919 Gamage catalogue.

Fig. 18: Detail from fig. 17 showing the

Gamage label on the device. The label reads, “A.W. Gamage

London”

15 Disc Model

The fifteen disc model was listed in company advertisements as

“The No. 2 Omnigraph” incorporating the same driver motor as the

other models, but with a more elaborate cam mechanism for

changing the discs (

fig. 19).

Fig 19: “Omnigraph No. 2” is the name the

company gave to the fifteen disc model. This instrument is

probably on a replaced wooden base.

A version of this model advertised in 1909 as “The Omnigraph No.

2 Improved” used a battery powered motor and rheostat in lieu of

the wind-up motor (

fig. 20).

Fig. 20: “Omnigraph No. 2 Improved” is the

company designation for the electric motor driven version of the

No. 2. Omnigraph.

An elongated drive belt connected the drive shaft of the

electric motor to the rotating platter. A total of 60 discs was

included with this model. At $10 in 1909, this amounted to

nearly a weeks’ wages for a typical worker, making the purchase

of this instrument a very serious decision. A slightly different

version of this instrument with a different design cam mechanism

also allowed for hand cranking (

fig. 21).

Fig. 21: Another version of the “Omnigraph

No. 2 Improved” with a different type of cam mechanism and a

provision for hand cranking the instrument. Notice the different

style discs with large holes. The author has never seen these

discs such as these and wonders if they were ever produced.

A slightly different version of the 15 disc model advertised as

“New Omnigraph No. 2” in 1910 employed the wind-up motor and

also had the capability of hand cranking the device if desired (

fig. 22).

Fig. 22: “New Omnigraph No. 2” from a 1910

advertisement. The 15-disc instrument could be powered by either

the clock motor or a manual hand crank. Notice the user wearing

earphones. Auxilliary equipment such as a buzzer or oscillator

must have been present and not illustrated.

As with the single disc device that has both motorized or manual

drive (figs.

10,

11),

the author wonders why the hand crank mechanism is included with

motorized capability. It is possible that the company knew that

the clock motors wound down very rapidly and that students

working in pairs probably represented a more efficient way to

use the instrument. In addition, a human could probably crank

the machine more forcefully, minimizing the slowing that

occurred when the cam mechanism moved the stylus from one disc

to the next higher disc.

A version of the 15 disc model exists that has the hand-crank

mechanism, and no motor drive, with extra stacked discs where

the motor would be

normally located (

fig. 23).

Fig. 23: Hand crank instrument with no clock

drive. This unique instrument was never advertised to the best

of the author’s knowledge, and contained 30 Morse discs with 15

in use and 15 spares. This instrument contained the unique discs

shown in (

fig. 5). (Photo courtesy of Mr.

Mike Feher N4FS).

The company also supplied a 15 disc device with a buzzer and

straight key, to the New York Wireless Institute (

fig. 24).

Fig. 24: Omnigraph #2 with integral key,

buzzer and provision for earphones. from a 1920 advertisement in

QST for the New York Wireless Institute. Similar to

fig. 13, except with 15 discs. Students

enrolling at the institute received this instrument according to

the widespread advertisements for the school.

Conclusion

The Omnigraph company advertised or produced at least 15 models

of telegraph learning devices over an approximately 30 year span

early in the 20

th century (Table 1). There may be

other devices or variations thereof not listed here that may

come to light, and the author would appreciate hearing about the

existence of any such devices from readers. It should be noted

that a number of the devices described (above) are known only by

their advertisements. Telegraph manufacturers in the early 20th

century are known to have advertised items that are completely

unknown today, and it is uncertain if they were ever produced (

8).

Devices similar to the Omnigraphs that appeared after the demise

of company had an incised wheel which would send “SOS”

repeatedly and were presumably of WW-II military origin.

Interestingly, in 1963, long after the demise of the company, a

device was advertised in CQ magazine identical in function to

the Omnigraphs (

9). It consisted of a

motorized circular wheel with the Morse code characters cut into

the edge. Amateur radio operators could have a custom message

(such as their radio call letters) cut into the disc as an

operating convenience.

Inasmuch as the telegraph keys, sounders, buzzers, binding post

hardware and the clock drives included with the Omnigraph

instruments seem to be items supplied to the company by others,

it is uncertain exactly what portions of the instrument were

made at the Omnigraph factory itself. The wooden bases,

the rotating platter, and the aluminum discs may be all that the

company actually produced.

The unique design of the Omnigraphs represented a continuation

of the 19

th century American tradition of

electromechanical innovation that also produced the universe of

telegraph instrumentation, fire alarm systems, stock market

tickers, nationwide time service systems, and innumerable other

devices.

Given the explosion of the use of telegraph following the

successful demonstration by Samuel Morse in 1844, and the

importance that instant communication played in the economic,

social, and military fabric of the 19

th and early 20

th

centuries, the Omnigraphs played a small but important role

during the declining years of telegraph.

Morse code takes advantage of the simplest property of an

electrical circuit: on or off. As such, this binary form of

communication may be rightfully regarded as the earliest form of

digital communication, and the necessary predecessor of digital

communication as we know it today.

Notes and References:

1. An Omnigraph catalogue c. 1930 listed the

company as ‘Established 1900’. The first Omnigraph advertisement

the author could locate was from a J.H. Bunnell catalogue from

1900.

2. No advertisements for Omnigraphs were found

after 1931 suggesting this year for the demise of the company.

3. Numerous radio and electrical publications

and equipment catalogues from 1900-1931 were employed as

reference materials and are too numerous to mention individually

4. Friedman, Neil D. A Clockwork Omnigraph; CQ

Magazine Feb. 1981 p. 7-9.

5. Martin, Fredric W (KI6YN). Personal

communication.

6. Elwood, John (WW7P). Personal communication.

7. Friedman, Neil D. Omnigraph Disc Codes; Old

Timer’s Bulletin of the Antique Wireless Association. Vol. 35,

No. 1. (Feb. 1994). p. 54

8. Reinke, Roger W. I’ll Never Forget That Old

Whatchamacallit; Old Timer’s Bulletin of the Antique Wireless

Association. Vol. 37, No. 1. (Feb. 1996). p. 39.

9. ‘Parks Code Wheel’; Parks Electronics

Laboratories Rt. 2 Box 35, Beaverton, OR. CQ. Vol. 19, No. 5.

(May 1963). p. 79

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The author wishes to acknowledge the kind assistance of Mr. Lynn

Burlingame (N7CFO), Mr. Mike Feher (N4FS), Mr. Neil Friedman

(N3DF), and Mr. John Casale (W2NI), Mr. John Elwood (WW7P), Mr.

Fredric W. Martin (KI6YN), and Mr. Roger Reinke for providing

references, photographs and historical materials, and Mr. Edward

Gable (K2MP) of the Antique Wireless Association for his

assistance accessing the AWA database.

THE AUTHOR:

David R. Pennes, M.D. (WA3LKN) is an advanced class amateur

radio operator and diagnostic radiologist living in Grand

Rapids, MI. Dr. Pennes collects and restores bugs and landline

keys.